The stories behind the lockdown: Kazakhstan against Corona

July, 2020

—

anvar musrepov

During the quarantine, Kazakhstan became the first country in the world to return to a full lockdown in a post-Soviet authoritarian manner.

On March 19, lagging two weeks behind the actions of EU countries, quarantine was announced in Kazakhstan. Schools, universities, and shopping centers were closed. Armored soldiers with military equipment and machine guns were placed in front of city entrances, as police checked all passerby’s, asking each person about their purpose for simply walking. Considering the low number of coronavirus cases at the time, many people agreed that the government reacted with unreasonably strict protocols. There were few infected patients, yet the military marked those territories, cordoned off neighborhoods at the foci of infection, and in some cases even sealed entrance doors to apartment complexes containing dozens of residents. Kazakhstani citizens didn’t have the opportunity to go outside, exercise or even go for a walk. Quarantine adopted an extremely totalitarian style, and for many, it seemed that the Coronavirus was merely an allowance for the performance of an authoritarian power.

The special local consciousness of people, based on the mythological perception of reality, gave rise to a large stream of fake news: from disinfection through a pagan shamanic ritual of fumigating the space with sacred grass, to conspiracy theories denying the existence of Coronavirus, and connecting the quarantine with the prolonged transition of power in the country. Back in the Soviet period, political mythology was a part of the folk art. The Kazakh state system of making decisions behind closed doors lead to a conspiracy vision of the world among many of its citizens. One of these myths, for example, tells of secret meetings in the underground halls of the President’s palace, where Nazarbayev conducts mystical rituals with the cabinet of ministers, before levitating at the moment of worship. The mythologization of power and undermined trust also impacted the effectiveness of the information campaign of COVID-19, leading many people to simply deny the existence of the virus, linking the quarantine to political manipulation.

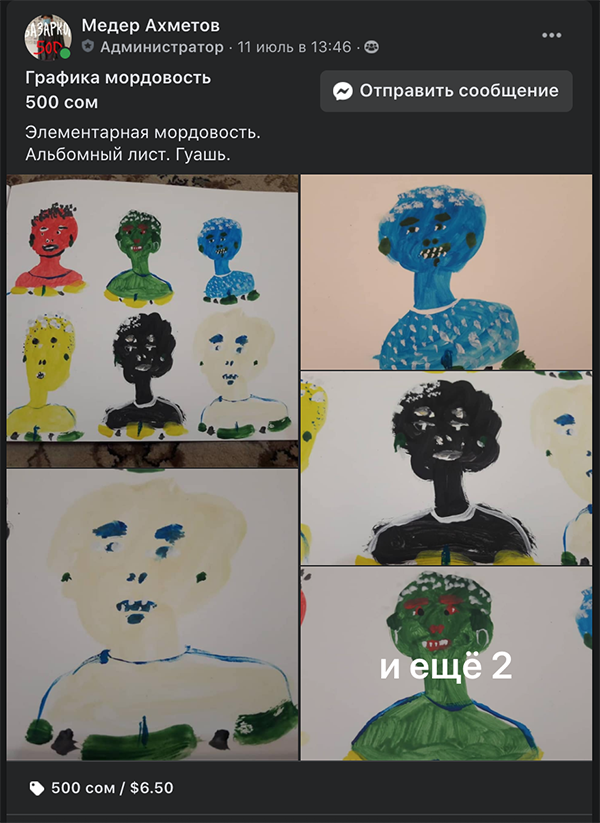

For a local economy built on the sale of crude oil, the beginning of the quarantine also marked the beginning of an economic crisis, caused by negotiations between Russia and the OPEC+ countries to limit oil production. The lack of work due to quarantine was accompanied by a sharp fall of the national currency, and an increase in the prices of goods and services. Under these conditions, the art community of Central Asia consolidated and created an alternative art market within a Facebook group. Initiated by Kyrgyz artist, Meder Akhmetov, Art Bazaar was inspired by the Russian community, Ball and Cross (Шар и Крест), but with a focus on artists from the Central Asian region. The principle of this self-organized art market resembles the schemes of financial pyramids common in the 1990s. When selling a certain number of works, a requirement is to purchase other art from the online bazaar, as well as transfer several works to the fund. In this way, artists bought and sold works from each other, creating a self-organized environment of collective care, while effectively excluding galleries and art market middlemen. It is fair to say that as such, the art market, as well as the institutional environment within the Central Asian region, is still in the process of formation.

So-called underground art in Soviet times emerged from cramped apartment exhibitions with the fall of the Iron Curtain in the 90s. The state, inheriting the Soviet mentality, has never represented culture by itself, and thought of art only in connection with the goals of biased propaganda. Artistic ideas that do not respond to the cultivation of sports or strengthening patriotism, won’t find their place among the bureaucratic “argumentation” of projects. The legacy of the Soviet art education which focused on socialist realism continues to present a major issue in academies and art schools. For a long time in these conditions, the community of artists developing an alternative to conservative art, in which the driving force were not institutions or the art market, but the enthusiasm of the community itself, remained in the margins.

Art Bazaar

But Art Bazaar was not the only reaction of the art community to the new reality of the pandemic. The curator of the Artcom platform, Aigerim Kapar, organized open workshops with a Georgian artist, Wato Tsereteli. Participants practiced collective drawing, which later resulted in a virtual exhibition organized by the participants themselves, presenting a webpage with the results.

Kyrgyz curator, Aida Sulova, conducted an educational program with children. The final works were accompanied by audio messages from authors, and were also presented in the virtual halls of the Artstep platform. I also decided to invest my part in the #stayhome movement and created an exhibition on the iada-art.org website; my idea was that an online exhibition should not mimic a real space, but could well remain in the webpage format, at the same time using the logic of an exposition construction. The name of the exhibition, Cybernomadism, reflected its main theme of examining the future from a decolonial perspective through the nomadic Kazakh culture. On the animated deforming grid background as a basic form of a space markup, works of 8 artists respond to the idea of technological utopia in the Kazakhstani context.

Cybernomadism

A. Kasteyev State Museum of Arts, which before the quarantine was a fairly conservative institution, has also gone through a transformation associated with the need to continue working online. The main exposition of the museum consists of Socialist realism paintings, and exhibitions of contemporary art were rarely held, unless in conjunction with other institutions. The need for a presence in the media prompted the museum staff to create exhibitions and record video tours. Realizing quickly that traditional art did not attract a new audience on the internet, museum curators quickly changed their strategy and began to focus on contemporary art. One such exhibition, dedicated to Rustam Khalfin, an artist who is often described as one of Central Asia’s contemporary art pioneers, was the first in the last 20 years. Isolation and a complete transition to online platforms have made many processes more transparent. This undoubtedly also influenced culture, as state museums moved away from the representation of the discourse of power and turned to the audience.

While the media space repeated like a mantra that “the world will never be the same”, by the end of April people were allowed to go for a walk, and by the end of May, cafes and shopping centers had begun to open. Simultaneously, repatriation flights were organized by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Kazakh embassies in different countries. Because of the bureaucracy and the general situation, many had to wait for two months to return. After arriving home, people were signed to a 14 day self-isolation, but no appropriate supervision was conducted and the arrival of citizens took place before getting out of hand.

Towards the end of June, the situation changed dramatically and got out of control. The dissidents’ opinion changed, and arguments such as, “show at least one patient,” ceased to flash on social networks. Instead, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and all other social media platforms became filled with requests for help; people looked for medicine, advice, or tried to call for ambulances. Subsequently, the Coronavirus hotline and paramedical services were left immobile due to overload. Hospitals stopped accepting patients, and even the simplest antipyretic drugs were in short supply. Pharmaceutical humanitarian aid from different countries were sold through corrupt channels at inflated prices. No more advertising was needed. The virus had touched every family in the country, and even Nazarbayev himself became ill.

The media space became filled with obituaries of deceased celebrities, politicians, and relatives. Huge queues of people spilled out of employment centers and morgues, despite the danger of infection. On July 5, Kassym – Jomart Tokayev, the new president, conducted an online conference wearing a mask, in order to announce a second lockdown. Later it was revealed that the shortage of drugs and overpricing were associated with corruption within the Ministry of Health, and several high-ranking officials were removed from their positions. After almost a month, the situation with drug supplies stabilized, and several new field hospitals have been opened. Statistics of deaths from pneumonia, after a long period of denial, nevertheless, were combined with the statistics of deaths from coronavirus. Now, people are used to wearing masks, and they are much less likely to sabotage quarantine rules, but many still hold secret weddings and funerals, despite the strict measures (which includes imprisonment for 10 years).

Kazakhstan was the first country in the world to return to a full lockdown. When the private becomes public, and health issues are no longer too personal a topic for discussion, the local becomes global and the deadly second wave in Kazakhstan is, in essence, a threatening warning to the entire world.

Anvar Musrepov is an artist and curator from Almaty, Kazakhstan.