Infrastructuring the Region: The City of Bor

Kineske železnice pozdravljaju srpski narod (Chinese Railways Greet the Serbian People).

A banner hanging on the side of the fence of the New Belgrade railway station.

Photo: Jelica Jovanović, April 2020.

In 2018, when the Chinese company, Zijin Mining, took over the RTB Bor Mining and Smelting Basin, many were left wondering about the direction of the basin’s future development, and what this development would mean for the region of Bor and the country itself. Given the role RTB Bor played in the development of the city of Bor, and especially within socialist Yugoslavia, the attention was justified. Furthermore, since the Belt and Road Initiative was announced a few years prior to this takeover, with various infrastructural projects being either announced or in development in Serbia by Chinese companies, RTB Bor’s concession became even more interesting in the broader context of China’s global networking, exporting and economic expansion.

How will the ongoing construction of the railroad Belgrade–Budapest and the announced reconstruction of Belgrade–Niš (with a huge probability of continuation towards Greece and Athens) affect the east of Serbia and the broader Danube basin, where several significant investments by the Chinese government are happening at the moment? What is the causality behind these massive endeavors, if there is any, and how will it affect the everyday life of the citizens of Serbia?

Current condition of the main railway station in Bor.

Current condition of the main railway station in Bor.

Foto: Jelica Jovanović, August 2020.

The railways in Serbia, as a major piece of the country’s infrastructure, have had a pretty uneven development and corresponding popularity. Depending on the era, the phase of construction, equipment, and maintenance, it would (or sometimes wouldn’t) have passengers, and at times could turn into cargo dominated routes. The situation is even more complex for the branches of this network going towards the mountainous regions, such as the region of Bor is. Initially, a narrow-gauge railroad would have be built, which would later be either readapted into a wide-gauge railroad, or dismantled and moved elsewhere. There are only a few short routes of the narrow-gauge railroads fully allotted to the tourist visits, on which the popular “Ćira” steam machine locomotive operates. With the increased deindustrialization, there are many pleas for repurposing the old and outdated routes for tourism instead of dismantling [it], maintaining a glimpse of hope that someday the industry will return.

The 1922 map of the railroads of the then newly founded Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes – later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia – features one small leg of the railroad, colored blue, which turns to the west in Zaječar, and seemingly ends in an empty field. Where it actually ends is the location of the Bor mine, which had already existed for at least 15 years before the map was made (the ore was discovered in 1903, after years of research).

The history of the railroad construction in the region of Timočka krajina is deeply interconnected with the development of the mining in Bor village: in the second half of 19th century, the Obrenović dynasty was very invested in developing the mining industry upon the belief that a poor country, such as the Kingdom of Serbia, needed to develop its mining sector, and consequentially build its economy from the raw materials it owns.

Map of railroads of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1922. Archive of Yugoslavia, АJ-37-12-81.

Map of railroads of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1922. Archive of Yugoslavia, АJ-37-12-81.

In 1946, the railroad Bor-Crni Vrh was completed. The fact that this was the first railroad built by the youth brigades of Yugoslavia speaks volumes to the importance of this region for the new socialist government. Although post-Cominform in 1948, when an imminent threat to the country came from the East and provocations occurred on the border with Romania almost daily, the production in Bor carried on, as the electrification project of the country depended on the ore mined in Bor. Due to the strategical importance of Mining and Smelting Basin Bor (RTB Bor) for the implementation of the federation’s development plans, the motorway construction quickly followed. Although the construction was technologically quite demanding and (anecdotally) this was the most expensive highway per kilometer constructed in socialist Yugoslavia, the motorway was built and opened in 1970s. This motorway took a significant portion of traffic from the railroad, signaling the beginning of what would be decades of deterioration by the 1990s, and eventual mismanagement of this infrastructure by the 2010s.

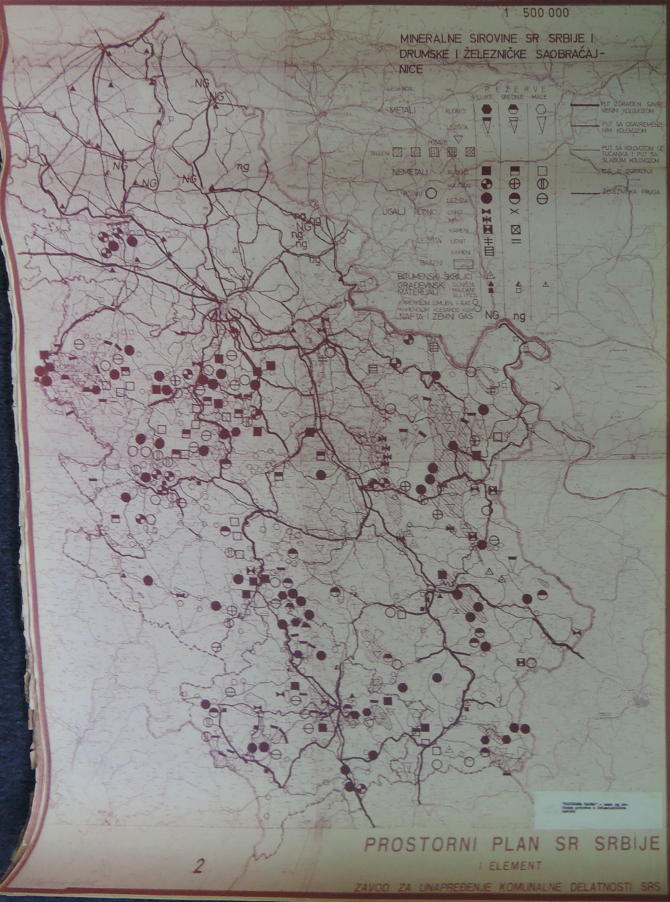

Spatial plan of Federal Republic of Serbia – map of mineral resources and railroad and road network. Institute for the Improvement of Communal Activities, cca 1966.

Spatial plan of Federal Republic of Serbia – map of mineral resources and railroad and road network. Institute for the Improvement of Communal Activities, cca 1966.

By the 2000s, the entire Region of Bor had sunk into decay due to the debts which had piled up during the years of crisis in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The regional infrastructure fell into disrepair and was close to gradually dismantling as problems accumulated, with pieces of the suspended railroad structure literally falling into people’s backyards. The disrepair was used as excuse to announce the removal of the rails, which came to a halt as soon as the announcement was made when the Zijin mining group came into the picture. The region grew considerably by this occurrence and is now being connected to the Piraeus Port development and trans-Balkan railway network reconstruction.

However, it appears not all of the infrastructure will remain – due to the expansion plans for the mine Novo Cerovo, the railroad to Majdanpek will be displaced (potentially the first of many).

Family Mikulović: the parts of dilapidated railway fell into their yard.

Family Mikulović: the parts of dilapidated railway fell into their yard.

The goal of the research is to map the developments and (dis)placements of the region’s railroad infrastructure and put it into the context of its historical and present-day developmental circumstances. Additionally, the research will try to outline the material and symbolic values of these infrastructures, both in their current conditions and at the peak of their use, and compare these to the promise(s) that came (and went?) with it. The research will be done in phases: archival, museum collections and library research; media outlets – newspaper, Internet, TV, etc; site visits; then finally, interviewing the relevant actors.

Core literature

Anand, Nikhil, Gupta, Akhil, Appel, Hannah (eds): The promise of infrastructure. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Arhiv Jugoslavije (AJ), Fond 187 – Savezna uprava za investicionu izgradnju

Arhiv Srbije (AS), Fond G-134 – Komisija za reviziju projekata

Kolektiv. List RTB Bor / List kompanije Serbia Zijin Bor Copper DOO Bor, no. 2276-2320. Bor: RTB Bor / Zijin Bor Copper DOO Bor, 2016-2020

Privredna politika Vlade FNRJ: Zapisnici Privrednog saveta Vlade FNRJ 1944-1953, vol.2. Beograd: Arhiv Jugoslavije, 1995.

Tomislav Mijović (ed): Razvitak: časopis za društvena pitanja, kulturu i umetnost, no. 1, 4-5. Zaječar: OOUR Timok, 1975.

https://istmedia.rs

https://www.solarismediabor.rs

http://www.zijinmining.com/business/product-detail-47443.htm

http://www.priv.rs/Ministarstvo-privrede/90/RTB-Bor-doo.shtml/companyid=387

Research has been supported by the Austrian Cultural Forum in Belgrade

Jelica Jovanović (1983) is an architect and PhD student at the University of Technology in Vienna, working as an independent researcher.