Biljana Ciric in conversation

with Robel Temesgen

On The Addis Newspaper—as a form of protest and care

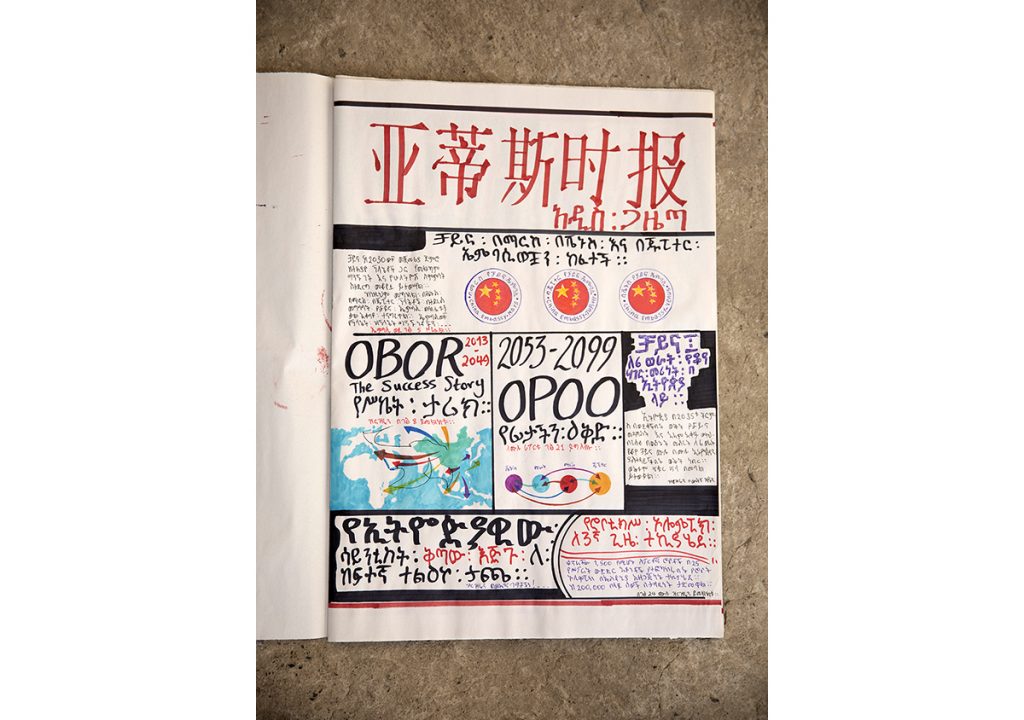

Addis Newspaper: The Chinese Issue – January 2050

Robel Temesgen is an artist working with different mediums from painting and performance to video. A project discussed in the interview is The Addis Newspaper series that he has been developing since 2014. For the project, Temesgen has been invited to create a special China Issue of The Addis Newspaper and the artist decided to situate the project in 2050.

In this conversation done in Addis Ababa in February 2020, Robel discusses the importance of newspapers within his practice, forms of silent protest, artificial care he has given to it, usage of Amharic language as well as Chinese presence and its binding capacity in Ethiopia.

The first stage of The Addis Newspaper – China Issue has been presented as a lecture-performance in Guramayne Art Centre as a part of the public announcement of As you go… project. Temesgens China Issue project is still ongoing.

February 1st 2020

Addis Ababa

Biljana Ciric (BC):

Let’s start with a question related to the newspaper. How did it come about and what does it mean within the local context, as it is a very locally embedded project?

Robel Temesgen (RT):

I started the newspaper back in 2014. I was in Norway back then doing my masters. At the time, local politics in Ethiopia had one of its pick moments. There were riots and the public was challenging the government, but the government also used harsh measures towards the people who criticized their actions. It was mostly about representation, justice and imbalance in terms of power (power was concentrated in one area of the country, while the rest of the country was forgotten). Many protests took place. A kind of action that was very common locally was the production of a big number of publications (newspapers, magazines).

BC:

Do you mean independent newspapers?

RT:

Both, they were mixed, at least before the protests. There were government-funded newspapers, but also independent ones. Independents were usually against the government and maintained that the government has introduced different types of laws against people criticizing the government. The recent example of that was an anti-terrorist act that was passed by the government, which could, potentially, put anyone who physically lives in the country into jail.

Anything you say could be taken as an action against the nation.

BC:

When was it enacted?

RT:

Probably early 2010. As I was away and I couldn’t access local news, I was dependent on social media; mostly Facebook and Twitter. Most of the content on social media had a very biased approach, the news could get fabricated and they were mostly personal opinions, or at least infused by them. It was impossible to grasp what was going on in the country. I would need to read quite a lot of news to get the essence of it. Besides that, many journalists got imprisoned, exiled, and newspapers shut down. In 2014 when I started the newspaper, there was a charge placed against six newspapers and magazines. Most of them either stopped publishing or had problems with distribution. You could print it out but you couldn’t distribute. Some of them went as high as 36 charges against one person. It was a very hard time for anyone who writes and publishes. For the diaspora, it was impossible to get an understanding of what was happening in Ethiopia. By that time I thought about what could be safe to write. To continue the act of writing, but stay safe from such trouble. The case of journalist/blogger Befekadu Hailu (በፍቃዱ ሀይሉ)1https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Befeqadu_Hailu, who was part of the blogging group called Zone 92https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zone_9_bloggers made me think about it.

When the government was taking them to jail, one of the evidence that came out for this particular person, Befekadu Hailu (በፍቃዱ ሀይሉ) was that he had a text written by someone else on his computer. It was never published. Just because he was in possession of it, he was charged for conspiracy. It made me think that machines like computers became an extension of our everyday life, as well as some kind of thinking tool. I have decided that I should write a newspaper that doesn’t get duplicated and distributed.

I was to do an act of writing and keep it locally, in my studio, in my own space. To pretend to protest while I am locked in my own house, an act of protest without raising my voice. I thought about what kind of content I should produce and decided that it should be something in between, a biased newspaper so that the content wouldn’t let you know if it is pro-government or against the government, does it contain facts or not. Complete chaos of truth, lies and accuracy. That’s how the newspaper started. Content of the first two newspapers reflected the situation of that time.

BC:

The first newspaper you have written in 2014 was a reaction to protests?

RT:

It was, in a way. Most of the content has been driven from my social media feed, I rearranged information that I gathered into the newspaper. The latest issue had a different shape.

BC:

How did you decide that the newspaper is the best medium for certain reflections?

RT:

The newspaper enables a particular approach and ways of dealing with the situation, that are specific to that situation – like the issue that we are doing now about China. It wasn’t my idea. The idea came from you and the project. The other newspaper project was related to Meskel Square3https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meskel_Square in Addis Ababa. I did an entire newspaper about the square. The idea came as a follow up on an exhibition project. The other newspaper issue was related to the time when the current prime minister was getting in power in Ethiopia and I decided that my newspaper should cover six months of that time. Depends on the circumstances. When I think about text material, such an elaborated and focused approach works best, so I choose to work through the newspaper. Research also becomes the final output, in a way, while in painting or other mediums that part of the process gets eliminated.

BC:

Can you talk about how to generate content for newspapers? Is there a methodology you developed over time, or does it always depend on the topic? Does the newspaper draw any historical reference, in terms of aesthetics of the local newspaper?

RT:

If you see my newspaper, it is mostly dominated by red and black. Colours that are very common for Ethiopian newspapers, particularly those of the socialist regime. There was one called Serto Ader (ሰርቶ አደር)4https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serto_Ader Amharic term for toilers, those who earn wages labouring. It was a socialist newspaper from the Derg period5https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derg (during the ’70s). The aesthetics of my paper were driven from Serto Ader, with the font that I have created.

Methods really vary. I make my editorial, distribute the content within the pages, choose the topic – it is quite a premeditated act. I would write the content, make a layout and then start to produce it.

BC:

Why are you using this specific newspaper from the Derg period as an aesthetic reference?

RT:

It has a very dry approach. The font is very upfront. Print and cost-wise, it has only black and red colour, but, at the same time, that goes back to Ethiopian orthodox inscription. When you use the word God or Trinity, Saint Mary, you would use red ink and the rest would be in black. During my childhood this was the type of newspaper that I would see in some houses – their walls were covered with this specific newspaper. It was also a strategy to distance my newspaper from contemporary ones (very colourful approach, specific fonts of Amharic used today) For me it was important to make it look dry. When I was younger we used to have a studio in my hometown in Dessie. We had a small business where we were making logos and advertisements written on the fabric. I had a very practical background that I could deploy very easily.

BC:

In terms of the content, usually it is not only social media feeds but archival finding and historical references that you are trying to combine?

RT:

Social media material was used for projects in 2014 and 2015. Later newspapers are done through research. In 2017 I produced 9 or 10 newspapers which were done by a process of making and copying or rewriting actual newspapers from the Addis Ababa archive. And these re-written newspapers are the last records of those that were shut down in 2014. I went to the National archive to see what is the official documentation of these (Lomi, Addis Guday, Fact, Jano, Enku magazines). I assumed that issues at the National archive are the last ones that the government looked into, and they couldn’t be found in peoples houses. I photographed them with the camera and took them to the residency program in Sweden. I sat and re-wrote the content of all of these newspapers (except for the advertisements). Sometimes I do this kind of archival work as well.

BC:

Does this archival issue have a title?

RT:

The title is always the same; Addis Newspaper.

In The prime minister Issue, I gave one to two pages to social media, but I’ve mostly decided for the issues of these six months that I wanted to address.

BC:

How do you distribute your newspapers?

RT:

2017 re-written newspapers were distributed through exhibitions. Most of them are not meant to be read. I made 100 copies of The prime minister Issue in silkscreen print so that people could borrow the newspaper, read it, and give it back to me. I was also inviting people to the studio to come and read them there. Through this kind of distribution, I also limit the access, in a way.

BC:

Why do you limit the access?

RT:

Hard question. Usually, once the newspapers are written, they are distributed, read and mostly forgotten. I wanted to invert this and give it a permanent state, artificial care, knowing that I write on very acidic paper and it will not last long. For example, if you expose it to the sun for 3 days, it will change completely. I use the recycled newsprint paper full of acid. I know that this newspaper will die at some point, but I, kind of, give it that artificial special care by limiting the access and not making it completely available and accessible, which goes in line with the act of writing. The act of writing the newspaper is a huge effort.

The idea of the newspapers is to be fresh and timely. You can’t have rotten news, it becomes information and not news anymore. Newspapers have urgency, you need to be accurate, respect the timetable and deliver. In my process, it is reversed. It takes time, it is very slow. For most of the cases, my newspapers don’t have the urgency of time, time is made elastic. Not only content but also process-wise.I have been writing, for example, the same newspaper for two weeks now, and it is still in progress. I have no urgency to finish and distribute it. I make my negotiations with time. Sitting down and writing with a pen is a different process from painting. If I make a painting, I know it will end up in a gallery or somewhere, and the newspaper will most likely stay locked. But I made an effort to sit down and write it, knowing that it will not get exposed and shown much.

BC:

The China Issue is the first issue that tries to anticipate or look in the future. What does looking into the future do to the newspaper?

RT:

Something very strange. It transforms it from regular to exotic – the handwriting, ink that is used, everything. To write about something 30 years from now faces many challenges. For example, how do you choose your wording, to begin with? Would you insist on the same way of distributing them? It makes me contemplate not only the material aspect, in terms of the paper and ink, but also how to produce the content. The only time that I have transcended through the time was the first newspaper I did, and it was going back in time (for example on one page you had news about a person getting imprisoned and on another page news about the same person being released). So it plays with time, past and present. This one is different. How to think about the future, what elements to keep, shall I just imagine our future as digitally and artificially manipulated one, or is there more to it? What are the parameters I should dwell on? I had to create a certain margin for the imagination towards the future. New challenge and approach to the newspaper.

BC:

We started discussing this project as part of As you go . . . the roads under your feet, towards a new future because of the Chinese presence in Ethiopia and the region through BRI6https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derg. You decided to try to imagine how the New Silk Road will look in the future. Why did you decide not to dwell in the present, but its 30 years later future?

RT:

The main reason was that I looked into materials that I could find and tried to make sense of them (reading, talking to people with expertise in trade etc..) and it got me thinking about how information is put out there and how the whole process is blinding, at least for me. The phenomenon of China’s presence in Ethiopia has a binding capacity. It is a very slow and aggressive process. My personal experience of China’s presence was, at first, cheap Chinese products, which then developed into road construction, government agreements and more construction, more trade, loans. The way it developed is not as threatening, as it doesn’t involve military presence. It is a very mild approach with only monetary exchange. So you can lay back.

But if you take a closer look and think about how this capital has affected local people and their mentality, it is a very complex and aggressive process. Materials that I looked into are Western-influenced media and they’ve tried to criticize the Chinese, but when I talked to local people here, most thought that this is a good potential and suitable approach for a country like Ethiopia, if we want to develop our economy. After that, I took a pause, as I realized I can’t comprehend everything through newspapers. I couldn’t pin a specific direction for looking deeper into the issue. I have decided to try to look forward, surpassing now, showing what we will look like in 30 years if we continue.

BC:

Your newspaper writes about a new stage of BRI project called OPOO (One planet One Orbit)

RT:

It is aggression. The BRI was a dream and it came to reality. The intention and obsession to outreach, to extend further, with trade and capital in the centre of it. My project anticipates that the current plan will not be enough, so it will have to be extended beyond Asia and Africa, exposing the urge to extend into orbit.

BC:

In the newspaper, you state that China is not a state anymore, but a new continent. So you propose a new geopolitical setting where a part of China is also in Africa and other places.

RT:

For me, there is undeniable power constructed and I try to not to be either a pessimist or optimist, but to exaggerate the influence that this power has. There is a potential but also challenges for poor countries that embrace the support.

BC:

Some pages are still blank and I appreciate this honesty of exposing a work in progress.

RT:

Some parts will remain empty. Those that you have seen will be filled. I don’t have to rush it into a cliché. I have to be honest and able to look at this content after 10 years. Even though I am presenting it as a lecture-performance on the 4th of February, I will keep working on it. To have that honest approach and vulnerability is important because I care about making it.

BC:

One important remark is that all the newspapers are written in the Amharic language. It reminds me of the work of Mladen Stilinovic where he refused to give lectures in English during his whole life. He made a famous work The artist that doesn’t speak English is not an artist. In newspapers from the future, you also make a note that Amharic, like Serbian and other languages, become local dialects.

RT:

In these newspapers, writing in Amharic can be perceived as a mild act of protest. It is to go against forgetting and to cherish the exoticness of it. Among other things, language is a means of comfort. And I want to feel comfortable when writing. In another aspect, it is to show that not every language is privileged to be perceptible to the eye of technology. To type Amharic on the computer is more complicated than languages like English or Norwegian.

BC:

How is the act of writing perceived within this newspaper? It almost sounds like an exotic, archaic gesture of the future.

RT:

The act of handwriting is very much about the physicality. There is this power and resistance in labour. And, on a very personal level, it is a reconnection to the reality of my upbringing where handwriting was dominant, be it in schools, advertisement or elsewhere. And I tend to like the aesthetics of it.

—

Full Newspapers can be viewed below footnotes. ↓

Robel Temesgen is an artist based in Addis Ababa.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Befeqadu_Hailu

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zone_9_bloggers

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meskel_Square

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serto_Ader

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derg

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belt_and_Road_Initiative

Addis Gazetta – The Prime Minister Issue

The news included in The Prime Minister Issue mark between Prime Minster Hailemariam’s resignation and the peace accord between Ethiopia and Eritrea. The five months period covered in the newspaper is apparently a time of enormous political changes and the artist composed the constituting “information” with travesty. As the aim of this issue was to avail the newspaper in the hands of vendors, artists Engdaye Lemma and Teimar Tegene were commissioned to make 100 copies of the newspaper in silkscreen.

Addis Gazetta – The Meskel Square Issue

The Meskel Square Issue was intended to serve as a collection of memories of one of the largest public place in Addis Abeba. The Square changed its name and purpose twice due to regimes. Originally named after its purpose at the time, Meskel means ‘True Cross’, as Orthodox Christians celebrated the finding of the True Cross. Later on, following to Derg, the Military regime took power in 1974, the structure and name of the square changed into ‘Revolutionary Square’, enlarged into 8.5 hectares, space was built into a half circled – amphitheatre with a podium for delivering speeches. Iconic events took place at the Revolutionary Square before the current regime took power and changed its name back to Meskel Square. After the EPRDF regime was in power, the significance of the place does not seem to decrease. The Square has continued its Social, Political, and Economic trajectories. These are the drives for archiving the history of the space through the Addis Newspaper.

Old News – 2014

Another Old News – 2015

Old News and Another Old News are the first works of their kind. Transcending between seemingly unrelated issues, these two newspapers attempt to deconstruct the notion of fact and news material. For the private sector, to survive as a news outlet has become about what reports to include and how to talk about those specific issues. Unlike the ordinary publications, these newspapers take a position of the in-between. Undefined standpoint. At a point, one of the contents would congratulate the government for winning the election 100%. In another hand, the news reports about one of the prominent journalist get freed from prison, yet it concludes the report by stating that the authorities have not announced the date of re-imprisonment of the same journalist, as if it is given that it will happen.