On Not Hearing the Gunfire

August, 2020

—

su wei

In the wake of the COVID-19 epidemic, January of this year marked the beginning of social distancing which was to last for months. During these months, China’s cities, towns, and villages were subjected to a strict system of control initiated and implemented by its bureaucratic institution. This system monitored citizens’ life and activities on social media, with the help of so-called grid management, big data, and a large number of officials “sinking” into the local community. This approach, on top of the voluntary self-surveillance of the public, did help to effectively stem the spread of the virus. Nonetheless, at the same time, inter-personal relations built upon local neighborhoods and communities—which had already been tenuous and fast-disappearing—were destroyed in the process.

The virus has confined people to their homes. In metropolises such as Beijing, such a singular state of affairs has turned the pandemic into an “information war”, as people are wrapped up in a world constructed by mobile phone screens. WeChat, a social media platform recently sanctioned by the U.S. government and long monitored by the Chinese government, has become the main channel for people to learn about the outside world and to express their complex emotions surrounding the pandemic. Because the platform itself can be both official (almost all official media has public WeChat blogs) and private, all the while being censored, public and private life become very closely intertwined in a bizarre and unsettling way.

This situation continues today, even while the pandemic has been declared to be completely under control in China. It is a moment in time when the world in your phone and your everyday life have truly collapsed into one another. Not only do you have to produce your “health certificate” on your phone whenever you go into a public place, but you also have to make conscious—even strenuous—efforts to discern valuable ideas and judgements from the more perilous ones when confronting messages and discussions on your phone from different friends and fields. Such discernment can be very difficult, even sometimes, schizophrenic.

At the end of January, and almost at the same time the outbreak of the epidemic hit its peak, I officially resigned from my job as a senior curator at an art museum in Beijing, in the hopes of rediscovering the fields beyond the staged scenes of power struggle. For a long time, I couldn’t leave my mobile phone either, although I knew how one-sided and biased the observations through it can be, and how expressions made through it could not avoid being performative, let alone being mostly improvisational and opportunistic by nature.

The art world has been squirming in pain after Chinese New Year. This pain first came from the capital world as well as the art market, and the online fair of Art Basel, Hong Kong matched this mood. The art world then brimmed over with discussions under the aegis of “art and pandemic”, with all kinds of undigested online creations and lecture series, each proposing new ways of thinking about our current context. To be fair, the art community has always shown a spirit of dissatisfaction with the status quo, albeit a spirit that is also sometimes rare, and has been consistently on the wane since the year 2000. Nevertheless, some of the recent creations and opinions continue to deeply reveal our misconceptions about contemporaneity, as well as how untenable this fragile, short-lived sense of the contemporary actually is. In other words, our sense of the contemporary cannot stand even the slightest interrogation, be it humanistic or that about the actual logic behind knowledge production.

What really gave me a strong sense of crisis was the outbreak of the BLM campaign. It spread across Chinese social networks at a lesser speed and with weaker intensity than the civil protest movements did several years ago, including the Wall Street movement, Hong Kong’s Occupy Central and the yellow umbrella movements. To explain our lukewarm reaction to the campaign, we need more than the simple fact that local social media platforms, such as WeChat, have not played an important role in China’s social life for very long. Not sufficient, either, is the fact that Facebook and Twitter have been banned for a while. Rather, the steep decrease in the communication effect of the BLM campaign reflects a change in people’s mentality. The Chinese cultural scene caught in various discourses of state, individuals, nation, imperialism, market, freedom, etc. is inevitably falling apart, and the once shared feeling for the oppressed has been substituted by that of defending national interests. In China, people have long regarded the race issue as a product of the United States, ignoring its pervasive presence among themselves. Moreover, debates about justice and equality have faded into the background, along with those between the New Left and liberals back in the 1990s – those debates have now rendered themselves footnotes to nationalist contentions where racial issues are concerned. The racist “scenes” and “misunderstandings” we all experience abroad are often reduced—in an alienating way—to “common knowledge,” and are often dismissed as irrelevant, as if they “only happen to other people.” It so seems that the issue of race is much less important than that of class, which apparently concerns more Chinese people. The value of such names as Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner and George Floyd invariably seem to be of secondary importance here.

As the confrontation between China and The United States—which began last year—has recently been radically escalating, a division between the left and the right is gradually revealing itself in the cultural sphere. Such a schism, however, was otherwise disappearing in the context of the neoliberal economy. The professedly more critical left constantly draw upon the historical legacy of the “first thirty years“ (1949-1979) in their interpretations of today, whereas the liberals are having difficulty negotiating a space amidst the ideological struggle between China and the Western world. Both sides are engaged in a tightrope-walking practice, the dangers of which, however, are again obvious: one either skids to the nationalist left or hits the nihilist right. Meanwhile, at the public level, nationalism has reached its zenith with government support, while the recent military confrontation between China and the United States only further aggravates the situation.

What is emerging in the cultural and public spheres imposes a strain on China’s art world. Admittedly, art inevitably exists in the world, but what better describes the situation is that the art community in China have been passively mobilized at this time – their motivation and self-awareness subsequently still subject to scrutiny. The nationalism and nihilism of the country as a whole have penetrated the art world on all fronts. Despite the fact that the Chinese art community does not often reveal their political stances—not an entirely conscious choice, though, since such practices can also be gestures of withdrawal—a certain collective unconscious is indeed being fashioned by the radical changes in the cultural and social realms. Globalization, though long proven to be problematic, remains the ultimate faith of many because it is so difficult to confront the local situation squarely – we find ourselves in desperate want of courage, motivation, and appeals when facing the local.

Though there are yet more problems. When immersed in the world within their mobile phones, the Chinese art community (unsurprisingly) shows yet again, a certain ‘bluntness’—or rather an insensitivity to the reality. Private conversations on WeChat or its more secure alternatives (sometimes one must avoid Wechat censorship) are often characterized by opportunistic arguments that can constantly shift grounds from the left to the right. Such arguments can hardly leave space for future thoughts and are often no more than vehicles for one’s moral superiority, and obsessive confidence in one’s own knowledge. For the art practitioners who are already safely middle-class, and even part of the high society, they are equipped with a strong sense of reality as a result of their frequent travels between East and West: their friendships with Western art institutions; their expensive apartments and cars in major cities including Beijing and Shanghai; the education privilege their children would enjoy; and not least of all, the skyrocketing costs of artistic creation in recent years. Nevertheless, in the meantime, the truly complex battles in the real world have been telescoped, and the struggles of real people in faraway places are condensed into manageable sizes. Such a simplistic approach to reality also leads to an intentional oversight or partial sight when it comes to value judgements: they would hold fast to a value that they identify with, such as “freedom” in abstraction.

Such is the art world in the cell phone. Self-proclaimed liberals spreading around excitable gossip about authoritarian governments. Some fantasize that they belong to the White middle-class and thus venerate the unfavorable coverage of China in the Western media. The more ambitious, on the other hand, fantasize that they are the country per se and earnestly devise all kinds of solutions to remedy the status quo. There are also many nationalists in the art world who embrace the “local” and “grassroots”, and regard them as localization enterprises – as a result, fully accepting the value system they entail.

But there is no protest. I do not mean protest in the sense of the dissent. We do not even need to mention the risks it involves to be a dissenter. I mean instead, that we lack the kind of thinking produced right in the middle of the quagmire named reality, and that we lack, even more, the ability to look squarely into the clues that has helped fashion today’s reality. Perhaps the present art community in China should first learn how to go to the streets: to participate in movements, to debate with others in complex contexts, to create tools to resist police assaults, and to put down their cell phones.

We can only point out, in a way that is rather pessimistic, that the art world in China teems with all varieties of performativity. The sense of the contemporary has not been fully internalized, yet one is already eager to demonstrate one’s superior knowledge. Such piecemeal knowledge, adulterated by various motivations and sophistication, are however not solid grounds for discussion. Behind such knowledge demonstrations are one’s appeal to power. One is adept at using one’s moral stance as a banner, or wielding it a weapon in attacking others. One sometimes does it with a loud battle cry, while at other times deliberately concealing one’s real stance. One can be good at posing as either politically correct or incorrect, depending on the situation, to enchant or to mislead younger art practitioners. One masquerades as a student in front of one’s seniors to gain resources, while acting as the authority in front of their younger peers to obtain power. All of these have been undermining the already rarefied atmosphere of art discussion.

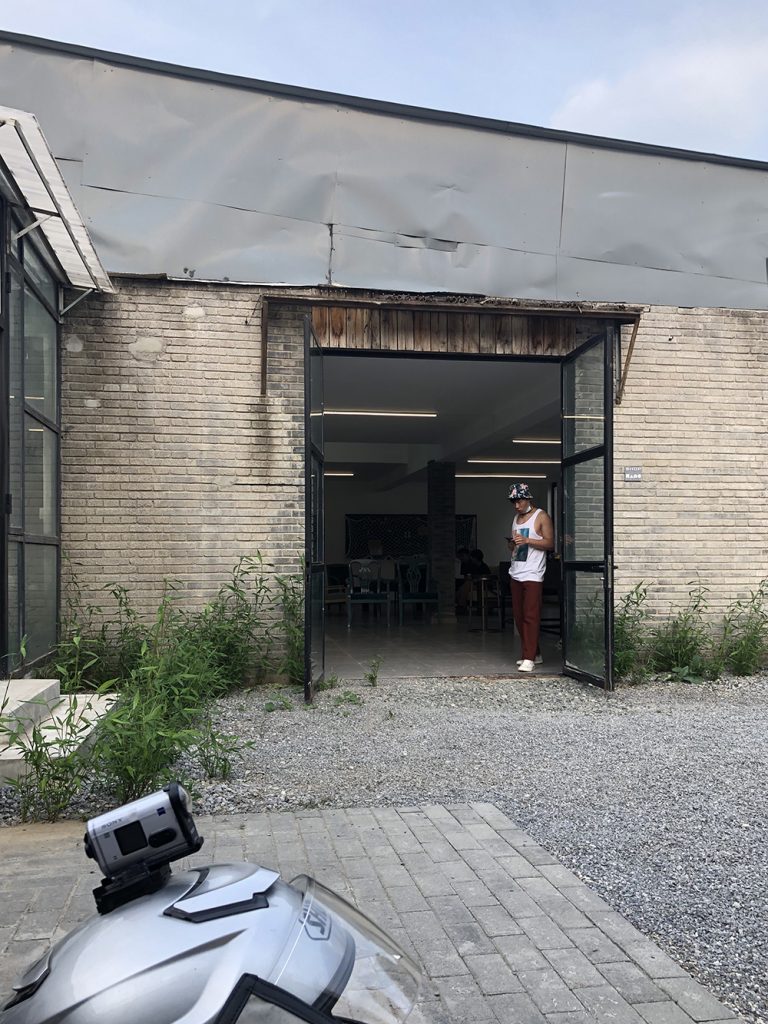

Some artists, however, chose to quietly rise against this absurd reality in the Chinese art world. Their agenda focuses on more physical participation, and seeks to carve out a space to think by giving away part of one’s self. Wu Wenguang, an independent documentary filmmaker, has been continuing his decade-long Folk Memory Project during the pandemic. The project titled “Passing Through,” registers the process in which Wu, in Yunnan, experiences a special period together with other filmmakers located elsewhere, with whom he has been working for a long time. The way they experience this together is called “online yoga”: they share their experience within a day, read poetry, or communicate other reading experiences and document their “time together” through film. Other artists, who may not have been well known in the Chinese art world, and who lacked exhibition opportunities, did not give up their artistic creation because of the pandemic or the pressure brought about by the survival pleas prevalent in the art world. Some of them work with a simple attitude and do not deliberately avoid real-life pressure. They polish their work in their own studios and through studio exhibitions initiated by artists themselves, thus finding a balance between art and reality. It is easier to experience a moderate sense of honesty, as well as palatable performativity, in such creations – especially when they are compared with certain works and exhibitions too eager to engage with reality. In addition, within the past few years there has been a number of artists and groups guided by left-wing ideas, who have used practices that intentionally provoke officialdom to give a voice to marginalized groups, and to find creative impetus in the private sector. Creations of such are promising, though they may still seem to lack a clear methodology and are not as satisfying in terms of artistic quality and creativity.

Outside of the art world, the online community Douban (www.douban.com) presents the convergence of diverse experiences and reflections of young Chinese from China and around the world. The vibrance it promises seems a world apart from today’s feeble and arrogant art world. Some cultural figures are also taking action. The official media ThePaper took the bold initiative to host a column dedicated to the BLM campaign, in which all points of view (including those by researchers) are cited and set to contest one another. Other media platforms such as Jiemian and Economic Observer’s Book Review (which have long been known for their focus on contemporary cultural changes and marginalized groups in China), have also endeavored to stage valuable discussions despite the atmosphere of intense political pressure.

These rare and precious actions salvage from the reality, a little space for the future. We cannot hear the gunfire from the battlefield, but we must understand that the gunfire is already everywhere.

Su Wei is an art writer and curator based in Beijing.