Accidental Knowledge: A Conversation with Lejla Hodžić

LEJLA HODŽIĆ IN THE SCCA OFFICE, 1998

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

Conversation between Lejla Hodžić, Biljana Ciric, and What Could/Should Curating Do? Curatorial Programme participants: Anne Liu, Beatrice Rubio-Gabriel, Christophe Barbeau, Devashish Sharma, Marina Savic, Xin Xiong, and Yujia Zhai.

Conversation conducted through Zoom on 6th January 2021 12PM CET/10PM AEST

As the program crosses over into 2021, we (partly) welcomed the new year together over our screens. The sun shines behind Lejla while some of us are in the lamplights of our bedrooms, already well into the evening. Among the many things that the pandemic has interrupted, physical togetherness has been but one of its notable victims.

Through the program, we have learned of and seen other interrogative artistic and expansive curatorial practices from other parts of the world, with a specific focus on the Eastern European context. Though we could not all be in Belgrade together, we gathered to speak to Lejla about her curatorial journey, her experiences with the art scene in Sarajevo and SCCA, as well as to see where she is right now in her practice and to speculate on how the art scene may develop in the future.

Devashish Sharma (DS):

Where did you grow up? How did your education in France at the Le Magasin in Grenoble shape your curatorial thinking? Growing up, did you have any architects, artists, or thinkers who you looked up to and wanted to learn from and emulate?

Lejla Hodžić (LH):

…I grew up in Sarajevo, I was born here…For my development, the ex-Yugoslav context was very important. From a very early age we were bombarded with different things. We watched a lot of films and foreign shows on TV or read the newspaper and had the possibility to see very interesting artistic things in person – from theatre [and] film, to exhibitions. The music scene at that time was [also] very important. Children’s TV shows in Yugoslavia had very alternative music. John Byford from TV Belgrade, an ex-BBC producer, produced several important shows with local new-wave bands (that influenced my generation)…The whole Belgrade artistic scene was there. We’ll come back to that – this kind of gathered-ness which existed in the 80s and 90s.

I [went] through normal, very ordinary schooling. I always wanted to be an architect so somehow, from [an] early age I was [already] preparing for that (going to [a] mathematic gymnasium). So finally, I’m not an architect, but I was into mathematics…I think mathematics and this world of science helped me in the sense that my brain became totally analytic in [a] different way. I was not artistically educated in the beginning, but my social life was totally about art and literature, music, and everything. From [a] very early age, I somehow, through my friends, through all these circumstances, gathered groups of people with similar interests and [at] that time, even though we were going out, drinking, smoking, whatever, we were also very much learning from each other. A lot of my knowledge from film and literature and arts are from that time. Nobody told you, “You have to watch this or learn that” but somehow you were interested to see, listen, and read…

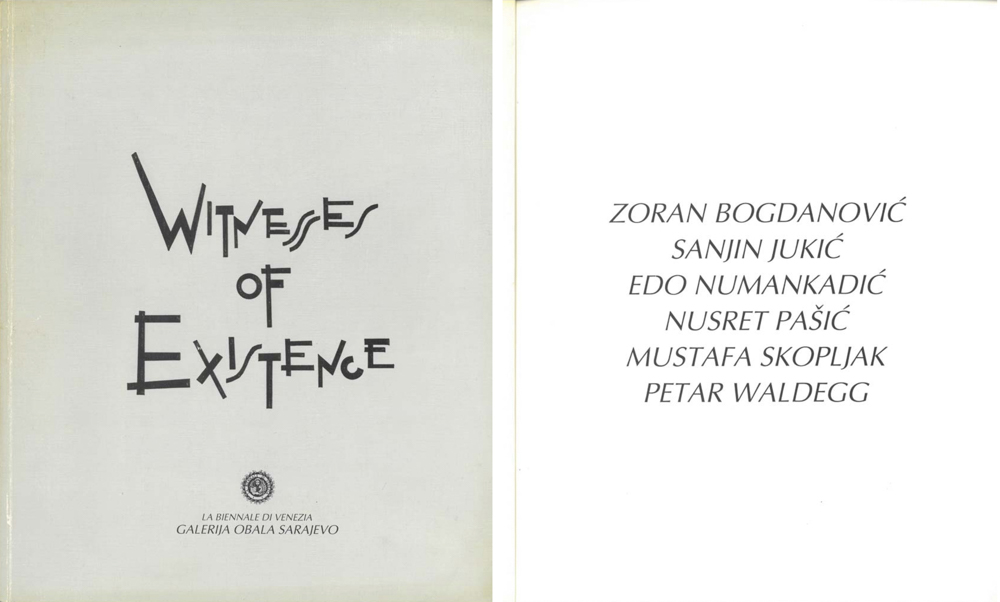

I enrolled in [the] Architecture Faculty after [the] gymnasium [when] I realized, Oh, I have [such a] small knowledge of architecture. So I started to buy different books. Everything that I could get in Sarajevo or Yugoslavia. Among those books for instance, [was] a book of essays about Robert Wilson, a very important theatre director, which was called Architecture in Theatre. It was gathered by one of the artists from Witnesses of Existence (1993), Sanjin Jukić, who did this pop art thing: Sarajevo-as-Hollywood. The book was not about the architecture, it was about theatre. I was totally amazed by those essays and by the works of Robert Wilson, and the way he built theatre plays as architecture. In that sense, you can see that this early education was not classical. It was composed of different spots of knowledge about different areas, which I think is very important…

There was this type of accidental knowledge, you know? Like knowledge that you get from different people, different media. Though now, in Bosnia, it’s totally different – and unfortunately, knowledge is no [longer] important…For instance, in the academic field, it’s not important if you are excellent in some field. It’s important if you have the best exam [results], that is the only key. And, here in this post-transitional country, you can buy that, you know? Unfortunately, in many places now, it’s not the most interesting curator with an interesting agenda or curatorial practice at the top of the museum. At the top of the museum is the political guy who is there because of some other interest…

Beatrice Rubio-Gabriel (BR):

So, is that why you decided to study in France? Did that shape your curatorial thinking? From what I understand, you studied architecture there, so that’s an interesting field to inform your curatorial practice.

Lejla Hodžić (LH):

After this time of the 1980s, the war started. I was only 19 when the war started, so I [had only been] studying for one semester. [It] was on [a] Sunday, I remember, it was the 5th of April. I was sitting with my friends; we were preparing an exam. [The] war started, but for us, we were still preparing this exam…There was this big demonstration in Sarajevo and the first victims. That was [the] beginning of the war. It was so strange because somehow, we were there – the war is starting – but we were like, we have exams, we have to prepare, blah blah. [Then] we didn’t have any more lectures. Everything stopped. [A] few months into 1992, a lot of my friends left Sarajevo. A lot of them, like [the] males, [went] down to the army, or they were taken to the army in that moment. Some of us continued to study but we didn’t have lectures anymore. We were doing projects at home, alone…

For the new year [of] 1993, I was invited to a party by the now Dean of Academy of Performing Arts. At the time, he was [a] student of [the]Academy of Performing Arts, [and] a friend of mine. I went there together with three of my colleagues from my lecture and that was place of Obala.

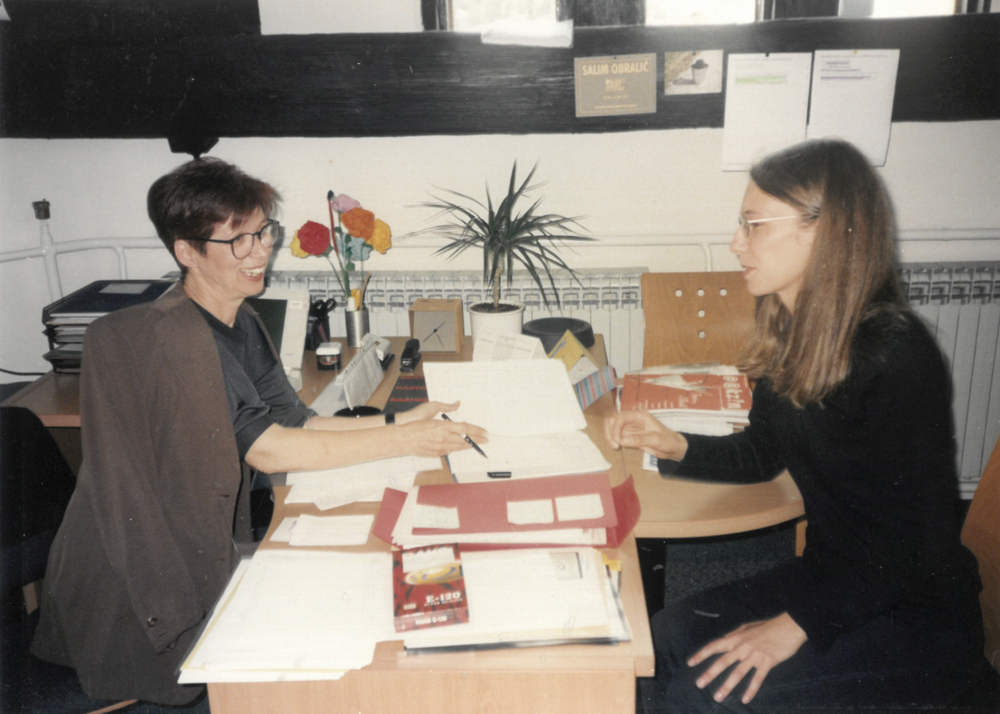

RED CROSS BUILDING/OBALA BUILDING, SITE OF WITNESSES OF EXISTENCE EXHIBITION, 1992

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

BR:

Who invited you?

LH:

Srđjan Vuletić, [a] film director. One of his films, I Burnt Legs (1993), I really like. What happened at Obala was that Miro Purivatra, who was [the] director of Obala Art Centre…said to me, “What are you doing, would you like to work with us, volunteering? I remember you, you were going to that concert. I remember you were at that film screening.” In that time, just before the war, at the Academy of Performing Arts in Sarajevo (called Obala also), there were a number of public lectures. Some of us who were in high school were going to the public lectures, on [the] history of film. We watched old films there…Somehow you [just] start to visit those places, you know? We were going to something everyday (concerts, lectures, theatre plays…). It was such a vivid scene in that moment. That was the accidental knowledge.

So basically, after the 1993 New Year, January 5th or 6th, my friends and I [began] to work at Obala and that’s how we [became] involved in different ways with this Witnesses of Existence (1993) exhibition.

WITNESSES OF EXISTENCE CATALOGUE, 1993

IMAGE: GALERIA OBALA SARAJEVO

BR:

Would you consider your first involvement in the art world in Sarajevo through Obala?

LH:

Yes. Obala was kind of the most important place during the war. Not only for me, [but] for [a] large number of the people who are now in their late-40s to mid-50s. That [was] the core for us, because that was the place [where] you had some 50-different people. You had to know, we couldn’t freely walk around – it was war. We didn’t meet every day. Occasionally, we all met there. It’s funny in that time, how we looked. We were [a] very small group of people. The offices in Obala were in the basement. It was kind of secure, you know? There was no shelling. For us, it was a secure place.

And then later, because I worked there in 1993 and 1994, I went to France. There (at Obala) I met Susan Sontag. I met with Sophie Ristelhueber. I met all these different artists and people who visited Sarajevo through Obala and through Miro. I went to France through them. I didn’t go to France because I knew what Le Magasin was. I didn’t, of course. When those people met me and some other of my colleagues, they very much wanted us to finish university.

BR:

So, did you work at Obala after you returned from studying in France?

LH:

No. Everything is before.

I met French writer, Jean Rolin in Sarajevo. Lot of French intellectuals were very much involved. They brought a lot of things to Sarajevo, not only humanitarian aid. They came several times to Sarajevo. They brought a lot of artworks, a lot of connections and so on, and somehow, they wanted me to continue to study. I was always fighting with Miro because I said, “No, I will stay. I don’t want to go.” They even made my passport without my knowledge with their connections, and one day, they told me, ‘You are going.’ I didn’t want to go. That was a big problem with my parents. Everyone wanted me to go, and I didn’t want to go.

SOPHIE RISTELHUEBER, JEAN ROLIN, IN SARAJEVO AFTER THE WAR, 1997

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

Then I finally did. They persuaded me to go. [There] was still [a] war – it was not possible to go from Sarajevo. So I went in May 1994 with the whole Obala crew when the exhibition, Witnesses of Existence (1993), went to Switzerland. I went out of Sarajevo with this plane with the UN. If I was Marina Abramović, I would now cry and explain how it was awful. But it was not, you know? It was very dangerous, but we had totally different things in [mind]. So, we went [by] UN transporter to this plane, [and] we sat in it on the floor. I remember that my best friend told me that was the first time she was in a plane. Ever. And she was on the floor in this kind of transport UN plane. We landed in Zagreb and we ate the first normal meal after 2 years. You know? We were all really skinny during the war. I mean, I’m skinny now, but I was skinnier then. I was totally depressed because I was going somewhere alone – to France. I don’t speak French [and yet] I came to Paris.

(LEFT TO RIGHT) MIRO PURIVATRA, LEJLA BEGIĆ, LEJLA HODŽIĆ, NUSRET PAŠIĆ, DŽEVAD MUJAN UN TRANSPORTER IN SARAJEVO, MAY 1994

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

LEJLA HODŽIĆ, MIRO PURIVATRA, MUSTAFA SKOPLJAK, ZORAN BOGDANOVIĆ, NUSRET PAŠIĆ, SARAJEVO AIRPORT WAITING FOR UN PLANE, MAY 1994

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

There I saw Sophie, Jean and all these French people who helped in Bosnia. They were all very important people, Deans of La Sorbonne and so on. They decided that I should go to Le Magasin, because Adelina von Fürstenberg was the director. They enrolled me. My colleagues in Le Magasin were people who finished studies, or finished a master, who were like 30, 36, and I was 19. I didn’t finish any university and I didn’t speak French.

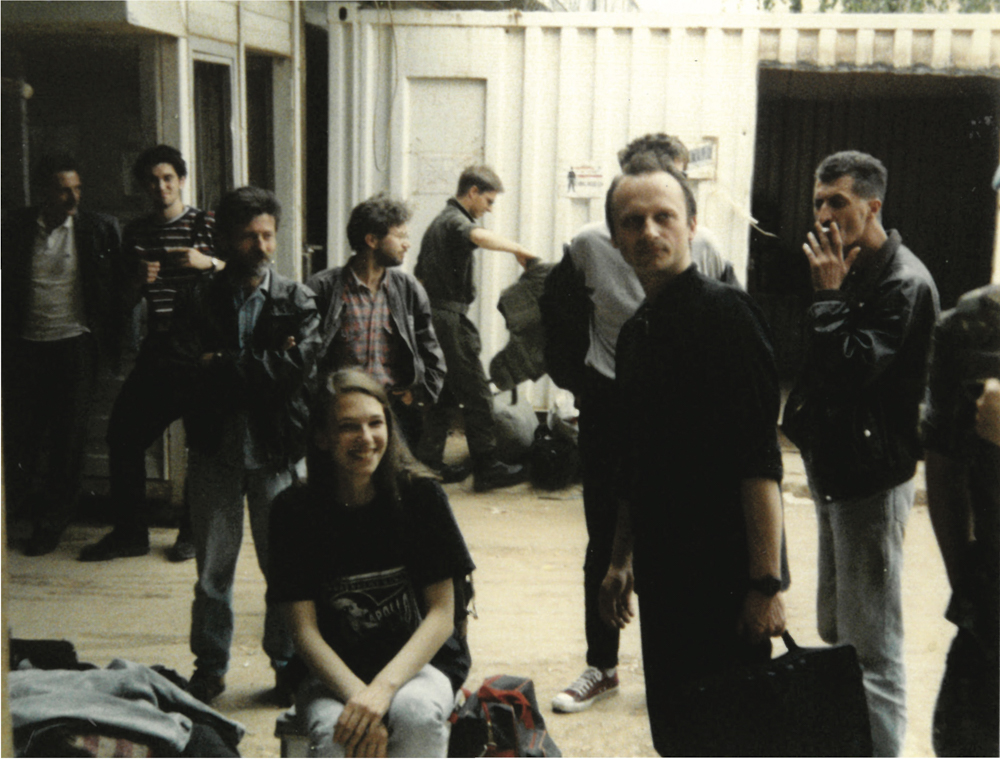

…Le Magasin was the first curatorial school of such a kind. In 1995, was this big exhibition of Aleghiero Boetti produced by Le Magasin [of] 100 carpets that he made together with the schools in France and Adelina von Frustenberg. The production cost so much over the budget so at one point she was arrested, you know? That happened while I was there and then suddenly the school was stopped. What was awful for me was that I got [a] scholarship through Le Magasin. Suddenly in 1995, I was without money, without [a] school in Grenoble, totally alone. Without [the] possibility to call somebody because there were no telephone lines with Sarajevo at that time. Nari Ward, a Jamaican/American artist, remained in Le Magasin producing a new work, so I started assisted him. That’s why Nari Ward is important for me.

NARI WARD, LEJLA HODŽIĆ, GENEVA, 1995

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

Marina Savic (MS):

Most people who leave the Balkans rarely return. So, what prompted you to return to Bosnia?

LH:

Oh great. Your question is connected, so I will just continue. I worked with Nari Ward, because he was an artist-in-residence, and he is Black, and I was Bosnian. We were very strange in Grenoble, because Grenoble [was] not a very open city. It’s quite racist, it’s very strange. We were strange people from this strange place in Le Magasin, this old factory. Nari Ward did a big installation. I was the only one from the school who had this knowledge from the war, of how to produce something without anything. So, for instance because all the money was suspended, we made 2000 invitations for that exhibition by hand using the stamps, as we didn’t have money for the printing.

NARI WARD EXHIBITION INVITATIONS – STAMPS, 1994

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

Meanwhile, Adelina who left France, invited me to work on her new project. She started this whole project by working with the United Nations, which she is still doing [with] Art for the World. She invited me after she went to Geneva, Switzerland. She was doing this exhibition [Dialogue de la Paix (1995)] for the 50th anniversary of the United Nations there. She invited Nari Ward and [Robert] Rauschenberg, Nam Jun Paik – all these big names. She needed somebody from ex-Yugoslavia, from the Balkans, so I was assisting her with this exhibition.

NARI WARD, SET UP FOR DIALOGUE DE PAIX, GENEVA, 1995

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

DIALOGUE DE PAIX ARTISTS, GENEVA, 1995

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

That experience of working with Le Magasin and Adelina, and working for a short while at the Centre Georges-Pompidou as an assistant in the Centre de Création Industrielle (which was at that time a very small part of Beaubourg), that is my connection to design. I worked there with the Chief Curator at the time, now Director, for the Japanese design exhibition. That was [a] way to earn some money and to survive there. Through this experience of working in Beaubourg and with Adelina, I learned a lot, but I was also missing the creative energy I felt in Sarajevo.

I was very young when I encountered the art world…I met, in those exhibitions, some artists that I admire who did the works by themselves. Adelina invited artists from all over the world…It was in the machinery of the United Nations. It was a very strange clash. For instance, Bosnian artists were not presented because the UN didn’t want to display works from Bosnia or from Bosnian artists themselves. All of this was disappointing for me, and I was thinking, it was not a question of money. That time in Sarajevo we didn’t have any money, it was wartime, you know?

I missed being part of something. I was there, totally alone. I had hundreds of friends, and I’m still in contact with them. Don’t think I was alone alone. I somehow even missed my parents, and I was never connected to them, but I mostly missed Obala. I missed the time that we had during the war which was incredible for me…I still hadn’t finished university at that time, but for instance, Miro, when we got electricity, showed me a theatre performance by Neue Slowenische Kunst. We were talking about Rauschenberg. We were learning through talking. It was this alternative education which I missed. [But] I loved my time in Beaubourg because my boss, Marie-Laure Jousset, was really great. She had the whole department in Beaubourg, and she said, “now is the time for them to learn English,” so everyone had to speak English with me – and you know the French don’t speak English. I loved Paris. I loved to be there, more than Grenoble, but I missed Sarajevo.

I didn’t immediately go to Sarajevo. I was invited by Suzy Meszoly who established [the] SCCA network [Soros Center for Contemporary Art], so I went to Budapest because she was a liaison between Adelina, myself, and a Hungarian artist, Antal Lakner. He did a very interesting work in the Dialogue de la Paix (1995) exhibition. Suzy Meszoly was already in the SCCA in Budapest. She was like [the] chief of all the SCCAs and she was preparing an exhibition about Sarajevo, but also about Slovenian art. In 1995, I was there when this Slovenian art exhibition was done. I met all these artists like IRWIN, Marko A. Kovačič, all of them. I was there for around 3 months. Suzy was a very kind person. I was living in her flat and I didn’t have any money. I was totally dependent on her, which was very strange. At one point, I just couldn’t stand it anymore, and I really wanted to go back to Sarajevo, even though Marie-Laure wanted me to go back to Paris. She even offered to get me a permanent job in Beaubourg. Somehow, I wanted to go home. I wanted to be home. I didn’t feel psychologically good there, especially in Hungary, so I came back. And I came back very strangely because I was very reclusive. I left Suzy’s flat from there, and I was alone in Budapest, totally alone without anyone, and I left. All these artists told me later that they were searching for me! That was totally shocking for them because I just disappeared. For a day I was in a flat with one girl who was working with me, and I only had one call to Miro and you [would] not believe: he was in Budapest. Somehow, he organized that I return to Sarajevo. It was the opening of the First Sarajevo Film Festival, October 1995 and I came with some guests. So, it was almost like in the films.

(LEFT TO RIGHT) MELIHA HUSEDZINOVIC, DUNJA BLAŽEVIĆ, LEJLA HODŽIĆ, YVANA ENZLER, SCCA OFFICE, 1999

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

Biljana Ciric (BC):

Lejla, can I just ask a quick question, did you meet Dunja [Blažević] in Paris?

LH:

Yes! I had already met Dunja in 1994 when I came for the first time. I met her in Place Vendôme in the gallery of Agnès b. We were not in contact in Paris. We just met and we had lunch together, but she remembered me when I came back to Sarajevo. Miro told me that I should study and that Obala was not a good place for me to work, because I have to make bigger things than just being an assistant at Obala. So, I started studying, and I worked in different cultural places at the time, like Czech culture place and radio. It was sour and sweet, my going back. It was not like I had imagined it would be…

I remember Dunja when she started to work at the SCCA [in Sarajevo], at the Academy. This was 1996. Miro and Dunja thought it was good for me to study, [rather than] work with her. For one year, I was just coming and having coffee with her. At one point, she was totally disappointed because she had some assistant[s] but was not satisfied. Some of them didn’t work. Somehow, I started to work and to study in 1997. For the first four years that I worked at the SCCA, I was also studying at the same time at the Academy…I realized that architecture is the field that I am interested in, but not my main one. I wanted to study the history of art, but at that time there was no history of art. Particularly in Bosnia. As I had experience in graphic design at Obala, and from the Nari Ward exhibition and some others. I made my portfolio and started to study graphic design. I am officially a graphic designer.

…I had a very strange education, in the sense that it wasn’t classical. All those people that I mentioned, and my experience of working with them, shaped and influenced me. Especially, all these experiences of being alone and travelling, which at that time was not so common, at least in Yugoslavia. My friends, they went with the family or with their boyfriends, [but] I was totally alone. When the war started, I didn’t want to go with my boyfriend like all our friends did. I was more independent in a sense. I remember that I didn’t want to leave Sarajevo, because I didn’t want somebody to tell me that I should leave Sarajevo – to force me. I said, “I will be killed, but I don’t want somebody to force me.” I did many things in life very impulsively. That’s how I left SCCA also.

LEJLA HODŽIĆ, DUNJA BLAŽEVIĆ, SCCA OFFICE, 1998

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

BR:

You mentioned starting to work with Dunja around 1997. We were wondering if you have any key learnings from that relationship, or key aspects, that influenced your practice?

LH:

Absolutely, I learned a lot. I think I am shaped by people with whom I have worked. Basically, it was in two ways. As I mentioned earlier [about] how I was introducing the scene to Dunja, during that time I also learnt a lot about curatorial practice and the way she works. I was with her every day for seven years, and I listened and saw what she was doing during this period in SKC [Student Cultural Center gallery, Belgrade] and then in TV [Galerija (1981-1991)]. Dunja was one of the key people who liked those very strange alternative shows on TV. The whole SCCA in Sarajevo was shaped through her experience of working with artists in the 70s and early 80s and from my experience of working in the war. When she was working in SKC, making the program, they had funding. They were not 100 percent supported by the mainstream, let’s say, but they had some funds and they could do projects. While in Bosnia, during the war, when Miro was leading Obala, he was always telling us, “Nothing is impossible, everything is possible. We can do it.”

I think that from my experience with Dunja, I learned good and bad things…I really love her. I still love her a lot. I think her basic problem, I guess it [comes] with the age, she couldn’t go with the times. It couldn’t only be the practice of SKC in Sarajevo, it should be changing with the times, listening [to] how the time shapes things. We had our first big quarrel about this Breakfast [programming series]. She thought it was nonsense. I was twenty-something. I knew that my friends, younger people, didn’t know about Russian avant-garde the way I [did]. They were not watching those films; they were not listening. They didn’t know who [Andy] Warhol was. I thought, we cannot expect someone in Sarajevo who is 20, to know Raša Todosijević. I knew because I watched TV, I listened to Miro, I was part of that scene. But younger people were not. So, we had to educate them. But in alternative ways, by chatting, like [how] we chat now. We had Breakfast like that. We had important artists who chatted and ate. That is a very beautiful way to feel comfortable, to ask questions. To feel closer to the people.

BREAKFAST WITH JUSUF HADŽIFEJZOVIĆ, SCCA SOBA, 2002

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

I used my experience of these strange things that happened to me in France, in Hungary, in Switzerland. I met people because I shocked them. Normally people are afraid to approach [me]. Now, I would not [go] to Robert Wilson, and say, “Hi, I am Lejla,” but when I was 19 I did that. I was not afraid. I came from the war, I am Bosnian, nobody knows me, I don’t care. Susan Sontag didn’t talk with me [how] she talked with some journalists. She talked with me, a teenage girl, and she said, “Oh you are 19. I had my son when I was 18. Oh, that marriage was awful…” She told me things that she didn’t even say in the interviews. I started to speak English with her. She said, “Oh, your English is perfect.” I didn’t speak perfect English. But she told me, “It is not important if you know the right expressions [but] if you know how to explain it”…

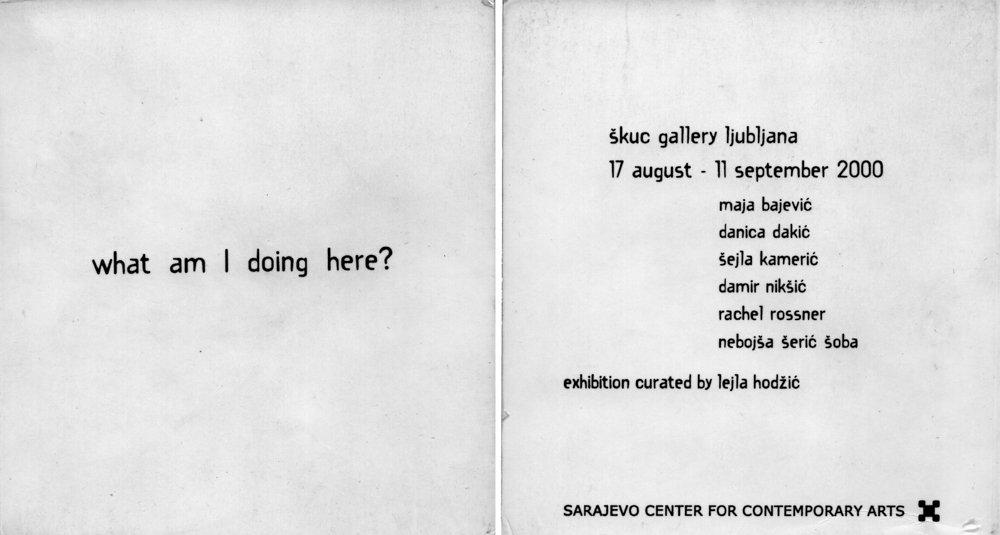

DAMIR NIKŠIĆ: WHAT AM I DOING HERE (2000)

IMAGE: GALLERY ŠKUC (LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA)

Christophe Barbeau (CB):

What was the first exhibition you did as a curator? You’ve spoken about working with artists directly to produce exhibitions, of finding strategies and ways to reinvent, and do something with very little material support, so I am wondering, what is the first exhibition that you considered yourself to be the curator of? From our research, the first time that you are credited as curator was with the exhibition what am I doing here? (2000) in ŠKUC Gallery in Ljubljana. Was there a previous moment, or is that the moment where you really took this role?

LH:

It’s very strange, I saw on [the] SCCA website that I am also signed as a co-curator in Meeting Point (1997), but that was Dunja’s. But you are right, I was always doing it. I was part of the team, but in SCCA only Dunja was curating. That was strange for all of us, [though] it was collective work in many ways. I got my experience little by little, working with different artists. I curated several individual projects and actions of the artists, like Šejla [Kamerić] and [Nebojša Šerić] Šoba, but they are not listed anywhere…Really the first exhibition that I signed, that I curated, was this project for Manifesta[3] (2000), a parallel project to Manifesta [3] (2000) in Ljubljana.

CATALOGUE WHAT AM I DOING HERE

IMAGE: SARAJEVO CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY ART

That was at the point where all these curators who are now very important on the scene, in the region, like Gregor Podnar, the WHW [What, How, & for Whom] curators, also started to do projects. I met WHW when they were students; I was leading some workshops and so on…Dunja had this thing while she was in SCCA that everything was under her. I was arguing with her a lot because I was thinking, she should let us do different things. But it was impossible in that moment and that was the first time I resigned. I didn’t make a catalogue of that exhibition. I made a notebook. I made something that people would keep. It’s amazing because, still, some people have it. I said, “I don’t want all this text inside that people throw away, I want something to have later.” I wanted to have artists together who were new, like Šejla, Šoba and Damir [Nikšić], and artists who are in that time just starting career, like international Danica [Dakić] and Maja [Bajević]. I wanted purposely to show these–I am missing the word–this rising up of female artists. But this exhibition is also questioning the moment in which we were…That was the question that all of us had, the artists and me.

ALEKSANDRA VAJD, ŠEJLA KAMERIĆ, LEJLA HODŽIĆ, 1999

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

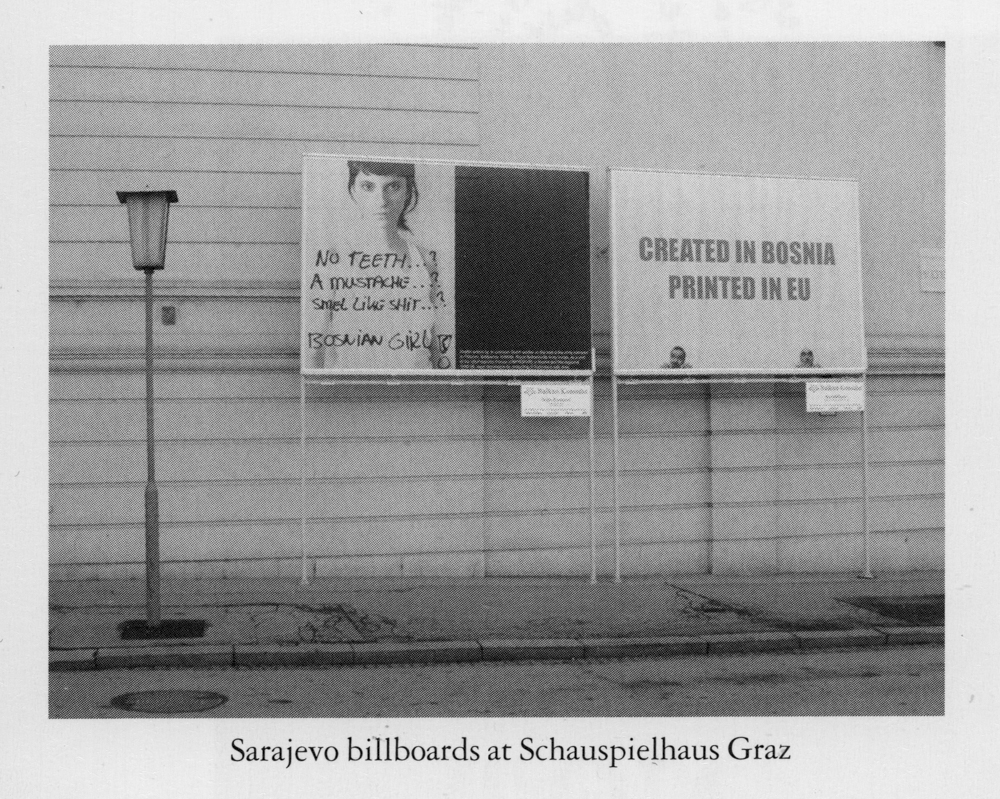

What is important to underline, [was that] the 80s and 90s were characterized by this gathered-ness. We were together all the time. We were working together all the time. I told you [that] I am [a] graphic designer, I am not curator. For me, as a kid at the time, it was very hard to say, ‘Yeah, I am curator, I will do the exhibition,’ and for Dunja it was very hard to acknowledge that. A lot of time you can even read [in] some interviews in Balkan Konsulat (2003), she says, “And I did the exhibition of Sarajevo which is curated by Lejla Hodžić.” She didn’t even come to see the exhibition. She was not mean, she was just like that because she was raised in [a] different system where: you are [an] art historian, you [get] experience, and then you start to curate and la la la. I [did] not fit anywhere, in any field. For me, that is the main thing, that I don’t fit…

CATALOGUE EXCERPT FROM BALKAN KONSULAT (2003)

IMAGE: SARAJEVO CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY ART

SET UP OF BALKAN KONSULAT EXHIBITION, GRAZ, 2003

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

And then I started this long collaboration with <rotor> Gallery…We did several projects. And I did several exhibitions in Sarajevo which were not dealing specifically with artists. I think the most important and interesting thing for me was this exhibition about memories…That was [the] exhibition (Culture of Remembrance) that I was invited to do by an International Theatre Festival MESS here…I asked all the participants, but also some of the artists, because it was [an] ex-Yugoslavian space, to choose one photo from that period of 1992 to 1995 and to write a small story about it. It could be any photo…I loved that exhibition very much. On one side was text, on the other, a small photo. You had to turn it. When you enter as a visitor, you enter in a kind of forest of these different stories which are fragmented. And all of them are making our memory, fragments of something which makes the whole story, like the exhibition what am I doing here? (2000)…

BALKAN KONSULAT, <ROTOR> GALLERY, GRAZ, 2002 (LEFT TO RIGHT: UROŠ DJURIĆ, BRANKO DIMITRIJEVIĆ, ANTON LEDERER, MARGARETHE MAKOVEC, LEJLA HODŽIĆ, ŠEJLA KAMERIĆ, NEBOJŠA JOVANOVIĆ)

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

Most recently, I think it was this exhibition about 75 years of ZAVNOBiH. It’s [the] 75th anniversary of [the] establishment of [the] contemporary state of Bosnia and Herzegovina. I did that in [the] Historical Museum, by making [a] photo archive of 5,000 photos from the Second World War. Digitizing it and putting it in segments: battles, heroes from Bosnia and Herzegovina, partisan monuments during the war, then monuments after the war and today…It happened with the war, people die. These people, some became heroes. So I made these segments, creating the story from the fragments…It was multidisciplinary because also at the opening we had a performance by one young dancer and actress, Amila Terzimehić. I don’t have a chance to do a lot of projects or exhibitions because all the doors here are (pause) it’s very strange, it’s the mentality, [as if] it’s better if nothing happens.

BR:

Have you noticed a shift in what it meant to be a curator? Reflecting on your role in Meeting Point (1997), where you observe this fluidity between artist and curator, do you find that how you see yourself as a curator has changed? Is there a difference between what it meant to be a curator then, and what it is to be a curator now?

LH:

I would not really call myself a curator (in classical way). It’s just one part of me. I had this intuitive knowledge that also came from observing things. It’s very important in different fields that I am working in, [this] wider context. I think that my role in Meeting Point (1997) was the same as in other exhibitions. It’s observing what is currently happening in that context and then trying to pose or answer some questions – that’s the characteristic. If you analyze all these exhibitions, the common factor was [that the] production of new works [was] by mostly new, young artists – so one could say that Margarethe Makovec and I, we are curators from practice. We were working directly with the artists. It’s not that we make alone some theme of the exhibition and then choose the works. We mostly produced exhibitions, together in conversation with different artists, realizing what may be the question in that moment. Then the artists made the project or the works for that specific exhibition. We very rarely used works which were already done…I didn’t do lots of projects. But I did almost all my exhibitions with new works of the artist.

SET UP OF MEETING POINT EXHIBITION, 1997

IMAGE: ALMA FAZLIĆ, LEJLA HODŽIĆ

LEJLA HODŽIĆ: SO CLOSE, AND YET SO FAR (1997)

IMAGE: SARAJEVO CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY ART

BR:

And has that stayed consistent? Is there something that you still practice whenever you do a show now?

LH:

I have to see to explain it (laughs). We did this exhibition BE REALISTIC, DEMAND THE IMPOSSIBLE! (2012) with lots of Sarajevo artists. We had around 30 artists included in the exhibition, and almost all the works were new works. That was the last big exhibition I made in this classical way…The most recent one that I mentioned (75 years of ZAVNOBiH), it’s not [a] classical exhibition. It’s more [of a] kind of art project with individuals who are not necessarily artists.

LEJLA HODŽIĆ, DUNJA BLAŽEVIĆ, LJUBLJANA, 1998

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

CB:

What you are describing is a methodology that is close to the one of the artist. You have always been close to the making itself. That might be why the distinction between artist and curator, or rather the way that you were curating the projects, was geared more toward new commissions. How was it when you shared with other curators, when you went to Manifesta 2 (Luxembourg, 1998) and met all the people working in the different SCCAs? Was there a transfer of knowledge or was it really something that was specific to your context and as you say, making something out of nothing?

LH:

Yeah, as I mentioned that time was very vivid, communications and lectures, lots of travel. I think it’s also what shaped all of us, spending a lot of time together. In very close ways, you know. I don’t know if I told you how I met these curators, how I became close to these curators, from MSE-projects (2000), Margarethe [Makovec] and Anton [Lederer]. Did I tell you this story?

CB:

No, no, no.

LH:

I have so many anecdotes. We were in this first meeting with Gregor Podnar. He placed us in a fantastic hotel. It was [with] these curators from WHW, Sabina [Sabolović] and Nataša [Ilić]…and then it was these two guys from Austria. We all had swap cards [but] they didn’t because they didn’t come on time. So…I talked with these Croatian girls and I said “Can I stay with you and I’ll give the two Austrians my room.” And they said, no! And I was shocked. I said to [the two Austrians], “If you don’t mind, we can sleep in the same room”. We just met, we didn’t know each other, but there were three beds, and it was fine, so we slept together in the same room. In the morning they left before I woke up, and I saw they took my soap [but] there was a watch. So the first email we got from Anton was, ‘Exchange soap for watch,’ and the second email was [an] exchange of the artist. So in that time, that was exactly the difference, [that] somehow you could see the psychology of the people.

They [WHW], no matter what, do really great things. They are educated, art historians, and they follow the rules, and they curate exhibitions in classical ways, you know? Anton and Margarethe have different backgrounds, one is [a] fashion designer and one is [an] artist. Them as curators, and me as a curator, we are very similar because we [come] from practice. We are breaking the rules.

When I was listening to Luca [Lo Pinto] the first day of your workshop, I was thinking [about] what he is trying to do with the museums – we did [that]. But we did it intuitively because we were forced to do it. We were forced to logically put the art outside of the museum. We reacted to the current situation in Sarajevo in that moment. For us, without this big structure of the museum, it was easy, it was logical, it was the main purpose. If you analyze the whole system now, there is this connection between arts and public, film and public, theatre and public. That is the question of contemporary society now. And somehow in this moment of the war – it probably created this specific situation – but people were aware of essential things. I think that’s the main point: essential things. Not really overthinking about the theory and this and that. We did it with the guts, you know? Lots of things, which sometimes are good, sometimes bad, but when you feel something, you have this artistic need to do something in that sense. I don’t know if I answered you (laughs)…

LEJLA HODŽIĆ, DUNJA BLAŽEVIĆ, SABINA SABOLOVIĆ, EDI MUKA, STOCKHOLM, 1999

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

…sometimes I think, especially in this lockdown, that my brain will explode because I simultaneously have so many ideas in my head […] That’s how I started doing these studies…because I wanted to write about not having the knowledge about costume design and doing costumes [but] how I did it [anyway].

BR:

That was actually one of our questions – we’re interested about what prompted you to move into costume design? I understand that there’s also a very strong presence of the performing arts and film there as well, is that one of the reasons you decided to shift over there?

LH:

Yeah, it was very strange, like all my life, in a way (laughs). Sometimes you have to go with the flow. When I left the SCCA so suddenly, I was fed up with persuading Dunja this, persuading Dunja that. It was very strange period, and it was [a] very stupid, basic thing. I was 30 years old, and I don’t know what happened to me [in] that moment [and] I very strangely left SCCA. Dunja said something to me, and I said, “Okay, goodbye,” and I left. I literally [left] like that, like in the movies. Without anything. I didn’t have a clue what I would do, you know? I was just like a spoiled child. I was offended by what she told me, and I left. I just left. I was too proud to think about anything and that was it. And that was the end for me.

I didn’t know what to do. I am this survivor type of person. I never did fashion, I never [made] clothes – only for myself and friends sometimes. In that moment, there was this new year’s fair, which was done by a friend of mine. I made a collection, what some designers would say. I very quickly did [some] skirts, but not normal skirts – skirts from two parts, which were each different and one could choose parts and combine [them]. I always liked to wear strange clothes. I went there, and I sold all the skirts. I was shocked. I immediately earned quite a lot of money. My parents were totally shocked that I left this secure job and salary. They were right (laughs). Somehow, I started my brand like that without thinking.

And then I made an alternative way of selling clothes, [like] doing pop-ups. I did this in Sarajevo in different places: in cafés, in this and that, and I started to live from that. That was maybe for one year, and at the same time, Jasmila Žbanić invited me to work on her first film Grbavica (2006), but I said to her, “I don’t have any knowledge about film or costume design,” and she said, “no, I know how much you know about film because you’ve watched so many films. You have a great aesthetic and I really want to work with you. I am a beginner, and you are a beginner, so we can do it.” And we did it. We had a very interesting way of working, because I didn’t have a classical knowledge of making costumes, which I realized later on, just how strange this was for other costume designers. For instance, for the first movie I didn’t make classical costumes for each scene. We had a very established leading actress, Mirjana Karanović. I created a wardrobe like an armoire. I created a closet of the clothes that the main character could wear, and I left it to the actress and the film director to choose for specific scenes. I proposed something, but I left place for trust. I’ve learned a lot during those 10 years, having a chance to work with a lot of different, very famous directors of the region. I am happy. Really, everything started from the one movie, then somebody invited me, and somebody else invited me, so I succeeded…Going into the costume design, it’s partly practical. That was the field that I could work in. When I stopped working at the SCCA, there was no place for me to work in art field in Bosnia. Already, Dunja was not loved here and there were no other places. The only way for me to work somewhere was to leave Sarajevo and at that moment I didn’t want to leave.

GRBAVICA (2006) FILM POSTER

BR:

Was it difficult being a curator within your local context or was it more that there wasn’t really a space to practice?

LH:

The basic thing in Sarajevo, from my experience…you have to know, there are no– for instance, the new Minister of Culture and Sports in Sarajevo, it’s a guy who is [a] basketball player, so what more to tell you? [The] previous one was a karate guy. He immediately cut the money for theatre. In that type of surrounding, to be freelance, alone, it’s very hard. I was not an art historian and anyone who came from Zagreb, Ljubljana, Belgrade with a degree in art history is a curator. I’m not curator to them. I’m not, even now, after all these exhibitions. When they see my CV, I’m not considered [a curator]. With the new, the young generation, yes. But with [the] older, no. I am a designer who doesn’t do graphic design. I’m not costume designer either, I mean, I didn’t finish costume design studies (laughs).

BR:

That’s so interesting, this idea of labelling and who gets to label.

LEJLA HODŽIĆ, URSA DRAZ, ŠEJLA KAMERIĆ, NAIDA BEGETA – OPENING OF BALKAN KONSULAT EXHIBITION, GRAZ, 2003

IMAGE: LEJLA HODŽIĆ

Xin Xiong (XX):

Considering what you have mentioned about how the present generation seems to have a disconnection with the current art scene, what do you think the Sarajevo art scene needs to move forward?

LH:

I think that it should be something like it was just after the war. Now, we have [a] 30 year difference. I think it’s important to find a new way to approach this younger generation. The same method cannot be applied [in] exactly the same way, but some principals of it can. It is important, this unconventional way of learning things…by talking with the people, spending time, drinking together, eating together…I think that individuality should be somehow encouraged but also gathered-ness. I think that’s the key. The art scene in Sarajevo was so strong in that one period because we spent all the time together and we influenced each other without knowing. That is essential for making change. All of that coming together and thinking about the problems and chatting…I’m sure, in three to four years, a group of people could change things. We are trying, [I] don’t think we are passive. I believe in these small steps and day by day (pause) I’m hoping something will change in the next years. I’m not sure, but I’m hoping…

—End of interview—

Lejla Hodžić was born in 1973, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Hezegovina. She graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts, Sarajevo, Department of Graphic Design. She works in the field of contemporary arts across fashion, design and curatorship locally and internationally (Obala Art Centre Sarajevo 1993-94, Sarajevo Center for Contemporary Art 1997-2003). She currently works as a costume designer for film and theatre.